Exodus

![]() Home A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Abbreviations Glossary

Home A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Abbreviations Glossary

Introduction

Relevance

Exodus is the name of the second book of the Old Testament as well as of the Torah (Pentateuch, Five Books of Moses). It means "going out" and was probably suggested by Exodus 19:1, where the Septuagint (LXX, the Greek translation of the Old Testament) uses exodou (genitive: "of the going out"), which was also taken up by the Latin Vulgate as the name of the book Exodus. In Hebrew, this book is called šemot ("names"), following the tradition of naming biblical books by the first word, or one of the first, in the book’s opening; in this case, “These are the names of the sons of Israel” (Exod 1:1).

The book of Exodus is pivotal for the Old Testament narrative and the faith that it sustains. In Exodus, God's double promise of descendants and land to Abraham and Sarah (Gen 12:1-3) is beginning to be fulfilled; Israel multiplies into a great people (Exod 1), and God initiates their setting out towards the promised land (3:7-8). In this book, God reveals the Divine name, Yahweh (the LORD<large style="font-size: 133%">), for all time and fills that name with its central meaning: Savior and Lord. In Exodus, the descendants of Jacob/Israel become a people with a special commission, established by the covenant relationship to Yahweh mediated through Moses at Mt. Sinai. In the context of this covenant, Israel commits itself to a new life governed by the Torah (Law) that has largely molded the ethics of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the cultures they have shaped. Finally, Exodus introduces the form of worship that characterizes biblical religion and its successors. The themes and patterns of the book of Exodus reappear in and inform much of the remainder of the Old Testament's writings and extend their faith-shaping influence into the New Testament and into our own time. (See below, "Issues of Special Concern to Anabaptists/Mennonites.")

Approach, Form, Style, Implied Reader

Canonical-Literary Approach. The approach taken in this article is a "canonical-literary" one. In other words, it regards the final, or canonical, text of the book to be a coherent literary unit. It studies this unit by way of literary analysis, using categories such as structure, form, character, plot, style, implied reader, and other literary aspects in search of the book's meaning(s). Since Exodus comes to us from the world of ancient Israel, however, historical, cultural, religious, legal, and other information regarding that world will often be required in the interpretive process. Further, the awareness that the present canonical text came into being through centuries of oral and written composition and transmission will also be kept in mind and will clarify some of the text's features.

Form. Exodus is a complex book. Its framework is prose narrative. Into it are inserted: (1) One longer poetic text (the Song of the Sea, 15:1-18). (2) Two distinct law codes plus additional laws, the Ten Commandments, 20:1-17, and the Book of the Covenant, 20:22–23:33; the laws of Passover and Firstborn, 12–13; and the covenant renewal laws, 34:11-26. (3) A long account of Divine instruction to Moses for building the tabernacle (25–31). These inclusions, however, do not stand apart as separate blocks of material interrupting the flow of the narrative, but have been incorporated into it and are firmly anchored in it.

Narrative Style. The strictly narrative sections vary greatly in style. The stylistic variations become clear when we compare: (1) The terse, fast-moving vignettes of Pharaoh's oppression and Moses' early life (chs. 1–2). (2) The extensive dialogue between Moses and God (3:1–4:17). (3) The dramatic encounters between Moses (and Aaron) with Pharaoh (5–14). (4) The depressing sequence of rebellion scenes in the wilderness, always accompanied by God’s grace (15–17). (5) The relaxed and familial reunion scene with Jethro (18). (6) The awe-filled theophany at Mt. Sinai (19; 24), bracketing two law codes. (7) The staccato events of rebellion and reconciliation (32–34). (8) The detailed but enthusiastic account of tabernacle building by a chastened people (35–40). All these sections, to name but the major ones, thrust the reader up and down on a literary roller-coaster moving in various directions and at unpredictable speeds.

Implied Reader. Who is meant to be the reader of the final, canonical form of Exodus? The book itself does not make this explicit. There are various cues, however, that point to a person I have called the "repeat-reader." This repeat-reader stands in contrast to the "first-time-reader."

The first-time reader—sometimes called the "narratee" in literary theory—is an imaginary reader who knows the story only as far as he or she has read into the book of Exodus. Such a reader would run into repeated difficulties. He or she would be confused, for example, by terms and items assumed to be known before their proper introduction in the story (e.g. the "[ark of the] covenant," 16:34; or the "ephod," 25:7). Again, the first-time reader would be confused by an account of Israel's march through Edom and Canaan after the crossing of the sea (15:13-18), when Israel has only barely crossed the sea at that point in the story.

The repeat-reader, on the other hand, is someone who already "knows his/her Bible," i.e. someone who not only knows the story preceding Exodus (i.e. Genesis), but also the rest of Exodus, and much of Israel's later story. This reader has no problems of the kind just mentioned; he/she knows the ark of the covenant or the ephod as parts of the long tradition in which he/she stands. For this reader, the final author(s) can introduce various features before their logical time in the story. For example, Aaron can already put a jar of manna into the ark before its construction has been commanded and carried out (16:33-36). The advance of Israel into Canaan, to cite another example, can already be proclaimed just after Israel passed through the Red Sea (15:13-18).

Further, the repeat-reader understands the text more fully than the first-time reader. While the latter might perhaps think of the new Pharaoh's fears about Israel's growing numbers as legitimate political caution (1:8-10), the repeat-reader knows that an enemy will indeed come; that Israel will indeed join that enemy; and that Israel will indeed escape. This reader also knows that this enemy will be God, and that the new Pharaoh is embarking on a collision course with God here already, even though God has so far hardly been mentioned. The repeat-reader, standing in the worship tradition of his people, will also readily be in tune with the author when the latter blends historical experience with worship practice (e.g. in the Passover account, ch. 12; or in the theophany account, ch. 19). Readers will find the distinction between first-time reader and repeat reader helpful at various points where the text would otherwise make poor sense [Narrative Technique].

Structure and Unity of Exodus

Can a unifying structure be discerned in the diversity of the final Exodus text? Commentators vary in their assessments. Historical critics focus on the prehistory of our extant canonical text, attempting to find explanations for the quiltwork of its formally and stylistically disparate sections in the coming together of various originally separate oral or written traditions [Source Theory]. More recently, many interpreters concentrate on the final, canonical text and find in it considerable literary cohesion, in spite of its obviously composite nature (e.g., Childs, Durham, Fretheim, and my own proposal below).

One test of unity is the ease or difficulty with which a clear structure can be discerned convincingly. Several plausible outlines suggest themselves immediately: Geographically, one could segment the story into (1) Israel in Egypt. (2) Israel wandering in the wilderness. (3) Israel at Mt. Sinai. Such a geographical structuring, however, remains external to the message. Or one could see a twofold division: (1) Exodus from Egypt. (2) Covenant conclusion at Sinai. Proponents of this structure tend to take either the Song of the sea (15:1-21) or the theophany at Mount Sinai (ch. 19) as the narrative’s dividing mid-point, and there are good arguments in favor of each. Yet a division into only two parts, whether correct or not, is insufficient to structure so long a book helpfully. Further, such a division tends to support the traditional but unfortunate theological separation of grace (exodus) and law (covenant). Several commentators have therefore chosen to sub-divide the book into a series of consecutive major sections, without attempting to discern an overarching and meaningful structural pattern (e.g. Childs, 1974).

To suggest an overarching structure is always a more or less convincingly super-imposed interpretive move (Janzen, 2009a). Without denying the validity of other approaches, I have taken my cue for the structure of Exodus from the twofold appearance of Moses' father-in-law, Jethro (or Reuel). Commentators have been baffled by his appearance in 2:16-22; 3:1; 4:18-19, and then not again until ch. 18, after which he disappears from the scene. In each case, Jethro plays the same role, namely that of the father figure and host receiving the fugitive(s) from Egypt—first Moses, and later Moses and his people—home into nomadic shepherd life (Janzen, 2000 [in further references, simply “Commentary”], on 2:16-22; 18:1-7,8-12; and Janzen, 2009a). In each case this homecoming is followed immediately by a theophany (at the burning bush, 3:1–4:17; and at Mt. Sinai, ch. 19) that catapults Moses and Israel, respectively, into a Divine commission for service not at all anticipated before. This pattern of events, as first experienced by Moses, clearly anticipates the fuller but parallel set of events experienced by Israel.

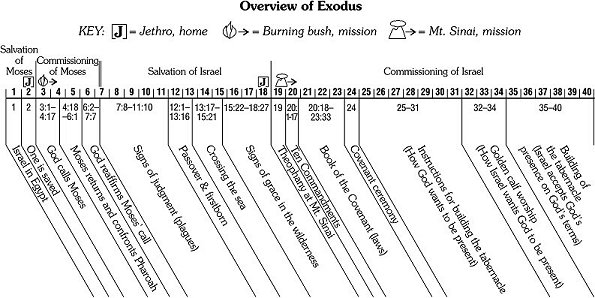

These observations led me to discern the following structure of the book of Exodus:

A. Anticipation (1:1–7:7)

- I. The Salvation (Deliverance) of Moses (1:1–2:25)

- II. The Commissioning of Moses (3:1–7:7)

B. Realization (7:8–40:38)

- III. The Salvation (Deliverance) of Israel (7:8–18:27)

- IV. The Commissioning of Israel (19:1–40:38)

(See Commentary, 18-22; Janzen, 2009a for fuller discussion).

This outline highlights God as the main actor. God saves and then commissions to service; this is God's agenda. God, Israel's rightful Master, wrests his people from the grip of the illegitimate master, Pharaoh. God's agenda and Pharaoh's agenda run on a collision course. Israel's agenda, however, also stands in some tension to God's agenda, especially from 14:10-12 on, when the people repeatedly brace themselves against their own salvation. Instead of joyfully accepting God's new initiative, the people waver between moments of trust (e.g. 12:50; 14:30f.; 19:8; 24:3; 35–40) and a persistent tendency to look back to the oppressive but familiar security of Egypt (e.g. 5:20f.; 14:10-12; 16:1-3; 17:1-7; cf. 32:1-6).

For two reasons, I have deliberately named two of the four major sections "The Salvation of Moses" and "The Salvation of Israel," avoiding the widely current term "liberation." First, "liberation" tends to suggest political-social freedom to be the aim of God's acting. Exodus is indeed a story of great political-social relevance, but it also transcends this as it leads Israel beyond liberation, into the new service of its rightful Master. Second, my use of "salvation"—a term occurring twice in Exodus: 14:13 (yeshu’ah; NRSV: "deliverance) and 15:2—is intended to link God's saving acts in the Old Testament to those in the New, for which Christians have often reserved the term "salvation." God's aim for Israel in Exodus is not of a lower order, but also aims at leading the people "all the way," as we read in the concise summary of 19:4:

- You have seen what I [God] did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles' wings and brought you to myself.

Exodus within the Tetrateuch (Genesis to Numbers)

The story told in Exodus begins in Genesis and continues in Leviticus and Numbers. To what extent, then, is the book of Exodus merely an excerpt from a longer narrative, and to what extent is it a story complete in itself?

Continuity. There are clear marks of continuity between Genesis and Exodus. They are concentrated especially in the opening chapters of Exodus, and then again in the final chapters. The book of Exodus begins with an introduction of the descendants of Israel that had followed their brother Joseph to Egypt (Gen 45–47). The first thing reported about them is that they multiply greatly, in keeping with God's creation promise (Gen 1: 28; cf. 9:1) and God's promise to Abraham (Gen 12:1-3, and often). When God takes the initiative to save Israel from Pharaoh, God does so because God remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (2:24; cf. 6:5), a covenant that included the promise of the land to which God would now lead his people (3:7-12; 6:2-8). When God introduces his new name, Yahweh, to Moses, God links it to the God of Moses' father(s), "the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob" (3:6; cf. 3:15f.; 6:2). The latter sections of Exodus, dealing with the covenant conclusion (chs. 19–24) and the rebellion associated with the Golden Calf (chs. 32–34), reflect and parallel the sequence of creation and fall (Gen 1–2, and 3ff., respectively. (Commentary, 368-70, 378-79; Rendtorff, 1993: 125-34).

The continuity between Exodus and Leviticus/Numbers is even more seamless. Leviticus and Numbers continue the legislation regarding the tabernacle, its priesthood and its worship, begun in Exod 25–31; 35–40, and report its implementation while Israel is still at Mt. Sinai. In Num 9:15ff., Israel is told to prepare for continuing the journey through the wilderness begun in Exod 15–17. In Num 10:10ff., Israel sets out on the continuation of that journey heading for the promised land, a journey continuing the grumbling and rebellion begun in in Exodus 15–17. Several characters introduced in Exodus also continue to figure in Leviticus and Numbers, most prominent among them Moses, Aaron and his sons, Miriam, and Joshua.

Distinctiveness. On the other hand, there are features that set the book of Exodus apart as a separate and complete literary unit. The structure suggested above demonstrates convincingly a thematic symmetry that conveys a sense of wholeness, balance, and completion: the oppressed—first Moses, then all Israel—are saved, and then immediately commissioned to become agents of salvation for others.

Other features also suggest wholeness and completion. Exodus introduces the Israelites as enslaved to a wrongful master, Pharaoh. The book concludes by showing the same people as freely committed in covenant to their legitimate Master, God. In the beginning, the Israelites do forced labor as builders for Pharaoh; in the end, they are builders again, this time building freely and enthusiastically for God. In the beginning, this God is apparently absent (chs. 1–2); at the end, the cloud of God's presence settles over the tabernacle in the midst of God's people (40:34-38). God has truly redeemed his people and brought them to myself, as 19:4 says succinctly (cf. also 15:17f.) Although the story moves on toward the promised land, a central transaction is begun and completed in the book of Exodus: The change of masters is accomplished, and the rightful master reigns in the midst of his loyal people. (Parenthetically, this completed arc from master to master and from building to building shows clearly how wrong it is to neglect adequate treatment of the tabernacle chapters when interpreting the book of Exodus, as is done so often).

Summary and Comment

Anticipation: Focus on Moses, 1:1–7:7

1. The Salvation (Deliverance) of Moses—Exodus 1:1–2:25 Terse storytelling and fast forward movement mark this section of Exodus. Jacob/Israel and his eleven sons have followed Joseph into Egypt. Their descendants have multiplied and become a great people there. A new Pharaoh, not knowing the story of Joseph, is alarmed and fears for his power. He tries to decimate Israel through hard labor. As this fails, he orders the two midwives secretly to kill all Israelite male babies at birth. When the midwives, fearing God, thwart this scheme, Pharaoh reacts with brute force, ordering all Israelite male babies to be thrown into the Nile.

Although anchored in historical memory, this story reduces details to what is essential. Few actors, a small stage, and an intimacy of interaction characterize it. Only two midwives serve the great multitude of Israelites, and the king appears to live right next door, talking to them without distance or protocol. Historical complexity is cast here in the simple mode of storytelling [Narrative Technique].

An Israelite couple has a baby boy. The mother hides him in a basket [literally: “ark”) in the rushes by the Nile, where Pharaoh's daughter finds him and eventually adopts him. She calls him Moses, and he grows up in the royal palace.

As an adult, however, Moses identifies with his own oppressed people. In his attempt to help them, he kills an Egyptian. As a consequence, he has to flee from Pharaoh's anger and escapes to the Midianites, a nomadic shepherd people in the wilderness east of Egypt. Thus he is, in a sense, retracing the way of Joseph, who had been forced by adverse circumstances to leave the nomadic shepherd life for Egypt. Welcomed into the home of Jethro (Reuel), priest of Midian, Moses soon marries Zipporah, Jethro’s daughter. She bears a son, whom Moses names Gershom, saying: "I have been an alien [ger] residing in a foreign land" (2:22 NRSV). Various versions and commentaries take the foreign land to refer to Midian and translate: "I have become an alien in a foreign land" (thus NIV). It is far better, however, to follow the NRSV reading, as above, understanding the foreign land as being Egypt (see Commentary, 48). Moses’ stay in Egypt was one of rejection and threat, while the story of his arrival and treatment in Midian has all the marks of a homecoming. Now Moses can settle down to a shepherd life like that of his ancestors before they followed Joseph into Egypt. Moses’ move prefigures Israel’s “homecoming,” also to be welcomed by Jethro (Exod18). Therefore, instead of calling this story “The Escape of a Refugee,” the repeat reader can already presage in God’s leading of Moses God’s comprehensive plan for the deliverance of all Israel.

But where is God in our story so far? Apart from one brief mention in connection with the midwives, God remains behind the scene. Yet several clues alert the reader, and especially the repeat reader, that God is at work to realize a larger plan for God’s people. First, Israel’s unstoppable increase, indicating the fulfillment of God’s promise of many descendants for Abraham, sets up the expectation of the coming fulfillment of God’s second promise to Abraham, the gift of the land. Second, a child (Moses) in a basket called an “ark” (tebah, like Noah’s ark; Genesis 8) floating on the Nile waters, although intended to bring his death, must surely be a sign of preservation. Finally, the repeat reader will recognize Moses’ “mini-exodus” as prefiguring the deliverance of his people in which he will be God’s central agent. To adapt Christian terminology, Moses, like Jesus Christ later, is the “first fruits” of those saved (1 Cor. 15:20; cf. 1 Cor. 15:20–24).

Meanwhile, the Israelites still in Egypt continue to suffer, even when a new Pharaoh ascends the throne. At the end of this section, however, readers receive a first explicit assurance that God has not forgotten them (2:23–25). The Israelites in the story, however, are not aware of this.

2. The Commissioning of Moses—Exodus 3:1–7:7 Having settled down to nomadic shepherd life, Moses tends the flocks of his father-in-law, Jethro, which takes him close to Horeb, the "mountain of God" (later also called Sinai). There he is stunned by a bush that burns but is not consumed. As he approaches, God calls to him: "Moses, Moses!" And he said, "Here I am." Then he [God] said, "Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground" (3:5).

Then God orders him to go back to Egypt to demand from Pharaoh the release of the enslaved Israelites. God wants to lead them to the land promised to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Israel will come to know this God of their ancestors by the new name Yahweh, the common modern rendering of the Hebrew letters YHWH (a form of the Hebrew verb hayah, “to be”), explained as "I WILL BE WHO/WHAT I WILL BE,” (a future form, preferable to the traditional “I Am Who I Am,” (see NRSV footnote, vs. NRSV text). This new name, to be used by Israel forever after, expresses God’s intention to reveal himself in a radically new way, and Moses is to be God’s instrument for bringing this about (3:7-15).

Moses, overcome by this theophany, resists his call by proffering various arguments for his inadequacy, including the claim that he has difficulty as a speaker. In response, a remarkably patient but totally unbending God tells him that his brother Aaron will be his spokesman, but insists that Moses must go. Overcome by God, Moses sets out for Egypt. On the way he is joined by Aaron. In Egypt, they share Moses’ commission with the elders of Israel, who are ready to accept it.

Next, Moses and Aaron confront Pharaoh and address him, in prophetic speech: “Thus says the LORD (Yahweh): Let my people go, so that they may worship me” (Exod 8:1). Pharaoh scorns this demand, saying: "Who is the LORD, that I should heed him and let Israel go? I do not know the LORD, and I will not let Israel go" (Exod 8:2). Then Pharaoh increases the burden and harshness of Israel’s forced labor. The Israelites are broken in spirit and blame Moses and Aaron for their increased plight. Moses, in turn, cries out to God. God, however, reaffirms his covenant promise to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to give their descendants the land of Canaan, saying: "I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and I will multiply my signs and wonders in the land of Egypt. When Pharaoh does not listen to you, I will lay my hand upon Egypt and bring my people, the Israelites, company by company, out of the land of Egypt by great acts of judgment. The Egyptians shall know that I am the LORD (Yahweh), when I stretch out my hand against Egypt and bring the Israelites out from among them" (Exod 7:3-5; emphasis added).

Realization: Focus on Israel, 19:1–40:38

3. The Salvation (Deliverance) of Israel—Exodus 7:8–18:27 A great "battle" between God and Pharaoh ensues (7:8–11:10). The contest is played out between the LORD (Yahweh) and Pharaoh who, intentionally nameless, figures as God’s Satan-like antagonist. Particularly awesome and fascinating is the employment of nature in God’s strategy of bringing ten “plagues” on Egypt. This is the commonly used English reference to various Hebrew terms such as “plague/pestilence,” “blow,” “strike,” “affliction.” The intent of these plagues in the present context, however, is well captured in the phrase “great acts of judgment” (7:4; see above). I will list them, therefore, as the Ten Judgment Signs (7:14–11:10):

- 7:14-24 First Judgment Sign: Blood

- 7:25–8:15 Second Judgment Sign: Frogs

- 8:16-19 Third Judgment Sign: Gnats

- 8:20-32 Fourth Judgment Sign: Flies

- 9:1-7 Fifth Judgment Sign: Livestock Plague

- 9:8-12 Sixth Judgment Sign: Boils

- 9:13-35 Seventh Judgment Sign: Hail

- 10:1-20 Eighth Judgment Sign: Locusts

- 10:21-29 Ninth Judgment Sign: Darkness

- 11:1-10 Tenth Judgment Sign Announced: Death of Firstborn Male

Pharaoh, although sometimes pleading with Moses (and Aaron), or bargaining and seemingly softening his resistance, persists in hardening his heart, refusing the Israelites permission to leave [Pharaoh’s Hardening of Heart]. It is noteworthy that these judgment signs respond to Pharaoh’s unjust oppression with abnormal nature phenomena, linking violation on the human plane with disturbances in the cosmic order.

Before the tenth plague strikes Egypt, however, God asks Israel to engage in the Passover ritual. Each family is to slaughter a lamb according to certain rituals, smear its blood on the door frame of the house, and eat all of its roasted meat during a night time meal. Everyone is to be dressed and ready for travel during this ceremony. Israel obediently and gratefully commits itself to its new Savior, the LORD (Yahweh), by observing the Passover rites. We note that, by doing so, the Israelites have been liberated in spirit, even though Pharaoh still rules externally (12:1–13:16). In that same night, the "Destroyer" goes through the land and kills every firstborn male in Egypt, whether human or animal. Only the Israelite houses marked with the blood of the Passover lamb are spared. This brings Pharaoh around to capitulate and let the Israelites go. They leave, richly loaded with “gifts” from the Egyptians.

Soon, however, Pharaoh regrets his decision and pursues Israel with a select chariot force. The Israelites find themselves caught between Pharaoh and the Red (or Reed) Sea and the Egyptian chariotry. They accuse Moses of having led them to their death. Moses, however, at the instruction of God, tells them: "The LORD (Yahweh) will fight for you, and you have only to keep still" (14:14). Then God opens a way for Israel through the sea, while the pursuing Egyptians are drowned by the returning waters. Israel, now freed from Pharaoh, sings a great song of praise (13:17–15:21).

With surprise, however, the first-time reader discovers that the defeat of Pharaoh does not yet end the Israelites’ captivity. Having been delivered from Pharaoh, they fall prey to their own lack of faith. Their wilderness march is beset by shortages of water and food, and by an enemy attack. Viewing their situation from a strictly human perspective, they despair and rebel. Again and again they murmur against Moses, accusing him of having led them into this plight. God, who overcame Pharaoh's hardened heart by great signs of judgment (the plagues), now begins patiently to overcome Israel's hardened hearts by great acts of mercy: water in a dry wilderness, manna and quails for food, defeat of enemies (15:22–17:16).

Finally Moses can bring his people to the "mountain of God," from which God had earlier dispatched him to Egypt. Here Jethro appears on the scene again, bringing along Moses' wife and two sons (Gershom and Eliezer). Moses reports to Jethro the great acts of God experienced by Israel, upon which Jethro presides at a sacrificial ceremony and a banquet of praise for God’s deliverance of Israel. Thus Jethro welcomes Moses' people to the shepherd life, just as he had earlier welcomed Moses. When Jethro, Moses, and the elders of Israel worship God together (18:12), the sign promised in 3:12 is fulfilled.

Earlier, Moses could begin a new and normal life routine in Jethro’s family (2:20-22; 3:1). Now Moses and Israel are helped by Jethro’s guidance to make provision for an ordered life in the future (18:13-26). When Jethro leaves, we feel that all is well with redeemed Israel (Exod 18:1-27). (Commentary, 223–29; Janzen, 2009a).

4. The Commissioning of Israel—Exodus 19:1–40:38

(a) Covenant and Law—19:1–24:18

Theophany (19:1-25). After the tranquil “homecoming” and settling into desert life reported in chapter 18, Israel is jolted into a new role by a unique encounter with God. Moses’ experience with God at the burning bush and his subsequent commissioning (3:1-12) is, in a sense, repeated here for all Israel. After a great theophany (experience of God’s holiness), accompanied by thunder, lightning, and fire proceeding from the cloud covering the mountain, Israel is called by God into a covenant and sent on a mission. It is to become "a priestly kingdom and a holy nation" to the rest of the world (19:6). This is to happen through a life centered on God, Israel’s rightful Master, in its midst (Sinai theophany, tabernacle), issuing in a life modeling holiness/otherness among the nations through obedience as prescribed for Israel in the Ten Commandments (20:1-17). The people tremble in awe and ask Moses to be the intermediary between them and God (Exod 19:18-21). Moses accepts this task and receives more laws and ordinances from God (the so-called Book of the Covenant, 20:22–23:33). Thereupon he leads Israel in a covenant conclusion ceremony that includes a communion meal and a blood ritual (24:1-11). Then he follows God's order to ascend the mountain to receive further divine instructions.

Law and the Decalogue (Ten Commandments; 20:1-21). With the Ten Commandments and the Book of the Covenant we enter the study of the vast and complex subject of OT law. It is of utmost importance, therefore, first to clarify certain crucial aspects regarding the nature and function of law in the OT.

1. More important than anything else is the place of the law in God’s leading of the people. Out of freely extended love, and in keeping with earlier promises to the ancestors (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob), God has set Israel free from Egyptian slavery and preserved it in the wilderness. Only then does God give Israel the law (Torah) and asks for a commitment to it in the context of the covenant. In other words, law follows grace; or better, law is a new form of grace. Law is not the basis of Israel’s salvation, but—just as in the NT—the invitation to respond to the salvation experienced.

2. The law, headed by the Decalogue, is there to map out the gist of the new life with which Israel is to respond to God’s salvation. All bodies of law in the OT, prominent among them the Book of the Covenant (Exod 20:22–23:33), Leviticus 19 and 25 (and other laws in Leviticus-Numbers), and the Deuteronomic Code (Deut 12–26), represent more or less detailed samplings or instances that illustrate how this new life might look, while none attempts to cover all areas of life.

3. The Decalogue also represents a sampling. Even though Christians often think of it as a charter covering all of life, many important areas of life are not represented in it. A comparison with Leviticus 19 is instructive. That chapter partly overlapping with the Decalogue, additionally includes laws providing for the poor (vv. 9-10), protecting the handicapped (v. 14), calling for love of neighbor (v. 18), and protecting the stranger (v. 33). All these concerns are integral both to OT ethics and to the teachings of Jesus, but they are not explicitly listed in the Decalogue. Thus, as already stated, the Decalogue wants to sample God’s will and not to provide comprehensive legal coverage.

4. This sampling and almost random (but see notes on You, below) selection of laws is also reflected in the literarily uneven appearance of the Decalogue’s commandments. Some are brief and terse, others long; some are negative, others positive; some have explanatory motivational clauses, while others do not. Scholars’ attempts to reconstruct a set of brief, symmetrical, and negatively formulated commandments (“Thou shalt not . . .”) have not been successful. Even the number ten, though intended (cf. 34:28), is not easy to apply. Catholics, Anglicans, and Lutherans, for example, count verses 3-6 as one commandment and divide verse 17 into two, while the Orthodox and Reformed traditions separate verses 4-6 from verse 3, and count verse 17 as one.

5. The Decalogue can, nevertheless, claim a certain preeminence over other law collections, a preeminence of function rather than of content (see Janzen, 1994:87-105. This is indicated by the following observations:

• The Decalogue stands first in the proclamation of God’s will at Mt. Sinai.

• According to Exod 20:18-21 (cf. Deut 5:22-33), it alone was spoken by God directly to Israel. All other laws were mediated through Moses.

• It is the only OT law code that is made up solely of absolute requirements, without attached conditions and prescriptions of punishments (technical term: apodictic law). The other codes include mostly laws stating specific conditions and punishments (case law or casuistic law, as for example, in Exod 21:28–32: "When/if. . . . then . . .").

• As mentioned above, the intended number “ten” does represent a certain claim to completeness (Heb.: "Ten Words," Exod 34:28). It suggests that we have here a complete and adequate sampling of God’s will, even if not a set of laws covering all areas of life. (For a position according the Decalogue an even greater foundational centrality, see Miller, 2009)

The Book of the Covenant (Covenant Code; 20:22–23:33). God’s instructions are expanded beyond the Ten Commandments to include a variety of “laws”, although this term may lead to misunderstanding. Exod 21:1 introduces them as mišpatim, “laws” (NIV) “ordinances” (NRSV), “rules” (JPS). While some may have functioned in judicial contexts, others may have been applied more informally. (Meyers, 2005: 180-182). They are transmitted to Israel through Moses, either verbally, or perhaps read from a text prepared in advance. The latter possibility is suggested by the reference to Moses reading "the book of the covenant" (24:7), a reference that has also provided the title for this collection.

Both the Decalogue and the Covenant Code outline, by sampling, the nature of the new life in covenant with God.. Some scholars consider the Covenant Code to be an exposition of the Decalogue. Fretheim states, “As a whole, it [the covenant Code] draws out the implications of the Ten Commandments, its introductory foundation” (Fretheim, 1991a: 239). But while there is some overlap of form and content, the two collections are also quite different from each other. Therefore I attach greater weight to the observation that the Decalogue primarily addresses life in the extended family (bet ’ab, "father’s house," as implied in 20:1-2, 4-6), while the Covenant Code primarily focuses on the welfare of the clan or village community (mišpaḥah, often mistranslated “family”). Thus the sampling of the new life under God is extended in the Covenant Code from Israel’s basic living unit, the extended family, to its next larger unit, the clan/village (Commentary, 253f.; 285-289). Probably Durham is right when he emphasizes that this Code is not held together by any consistent organizational pattern, but rather by the theological assertion that all these laws are Yahweh’s will for the people committed to him (Durham, 318).

The Book of the Covenant (Covenant Code) contains some absolute commands (apodictic laws, like all those in the Decalogue), without attached conditions or punishments (especially in the second part, 22:21–23:19). The first part (21:1–22:20), on the other hand, is characterized by case laws (casuistic laws), prescribing specific judgments in carefully defined situations. The Code shows no fully clear and generally accepted subdivisions. Some interpreters find in the Covenant Code a systematic interpretation of the Decalogue, so that its subsections relate to specific Decalogue commandments, a view that is not convincing to me.

A striking feature of the Book of the Covenant is the close resemblance of several of its laws to laws found in extra-biblical ancient Near Eastern law codes, most famous among them the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, from ca. 1700 BCE. These other codes consist of laws governing daily life, or civic laws. By contrast, the civic laws in the Book of the Covenant are framed (20:23-26; 23:32-33) and interspersed with (e.g., 22:28-31) religious prescriptions. In Israel, right living always considers both God and neighbor. Other important differences from ancient Near Eastern codes are the Covenant Code’s high valuation of life as compared to property; the way it downplays class differences, although the existence of slaves is recognized; and the virtual absence of bodily mutilation as a form of punishment.

Some of these distinctives are undoubtedly due to the impact of Israel’s experiences of God’s revelation, especially the deliverance from Egypt. It would be a mistake, however, to overemphasize the differences between these OT laws and their ancient Near Eastern counterparts. Israel lived in the same geographical and cultural context as the surrounding nations and consequently faced many similar situations and problems. In cases where certain ancient laws had helpfully regulated life for some of these nations, there was no reason why Israel should have distinct provisions. Such laws constituted God’s will, whether or not the peoples living by them knew and worshiped the one God. Thus they were properly incorporated into the covenant stipulations and placed under Mosaic authority.

In general, the Book of the Covenant reflects clan/village life after Israel’s settlement in Canaan. It presupposes sedentary agricultural existence rather than nomadic life. In its present form, the text gives particular attention to proper judicial practices and decisions for use “at the [village/town] gate,” in the context of the assembled men led by the elders (cf. Deut 21:18-21). There is no reference to a king, nor any evidence of royal administration. These features may be due to the Code’s early time of origin, even though it may have undergone changes in its textual transmission before canonization.

Covenant Conclusion (24:1-18). Chapter 24 takes up the story line from chapter 19, where the people, awed by God’s majestic theophany, hovered between fear and fascination at the foot of the mountain. This chapter treats Israel’s formal entry into its new commitment to God and its new covenantal mission. In its first half (vv. 1-11), the foundation for this commitment is laid by Israel’s pledge to covenant obedience. A blood ceremony and a communion meal seal this pledge. In the second half (12-18), Moses is singled out for a yet closer encounter with God. Accompanied only by his servant Joshua, he ascends into the cloud cover of the mountain to receive further instructions, together with the tablets containing the commandments of God. Meanwhile, the people, under the temporary leadership of Aaron and Hur, watch the mysterious, cloud-wrapped mountain from afar.

(b) Tabernacle and Golden Calf (25:1–40:38)

The Narrative. Israel’s encounter of God’s holiness (Exodus 19) and the people’s solemn commitment to the LORD in covenant obedience (chapter 24) initiate a relationship meant to extend into the distant future. The God revealed to Israel in the exodus and at Mount Sinai wants to be with them throughout all generations. Israel will remember this through the use of God’s newly revealed name “Yahweh” (Exod 3:13-15; 20:1-2) and the recital of the acts of salvation and covenant conclusion associated with it. The reality of God’s presence, however, is not sufficiently vouchsafed by historical memory. It is also to be embodied in tangible symbols as concrete as the water of baptism or the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper are for Christians today. God reveals such symbols in a vision to Moses when the latter has entered the cloud of God’s presence shrouding the top of Mt. Sinai. These symbols center in the tabernacle.

Two lengthy Exodus texts introduce the tabernacle to us: the Instruction (Exodus 25–31), and the Implementation (35–40). In the Instruction, God tells Moses on Mount Sinai: “[H]ave them [the Israelites] make me a sanctuary, so that I may dwell among them” (Exod 25:8). Then God outlines in detail what this sanctuary should be like.

Meanwhile, however, the people at the foot of Mount Sinai urge Aaron to build them an idol in form of a golden calf. They say: "Come, make gods for us, who shall go before us; as for this Moses, the man who brought us up out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him" (32:1). God’s work of salvation from Egypt is here retroactively portrayed as a failed effort of the man Moses! By this turn to idol worship, Israel commits its first covenant-breaking act, even before God is finished giving instructions to them through Moses. As punishment, God sends a plague upon the people, but on Moses’ intercession, God shows mercy, has Moses re-write the tablets of the law which the latter had broken in anger and despair, and grants Israel a covenant renewal (Exod 34:1-10).

Now the building of the tabernacle can begin. In the Implementation (chs. 35–40), Moses invites those who are "of a generous heart," men and women, to volunteer their offerings and skills for this task. A chastened Israel responds with an outpouring of contributions and voluntary work. When the work was finished, "the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle," and God’s presence dwelt among the people throughout their wilderness wanderings (40:34-38). Thus the tabernacle becomes the anti-type to idolatry. It is the archetypal embodiment of God-willed worship, in contrast to self-chosen human worship as represented by the golden calf.

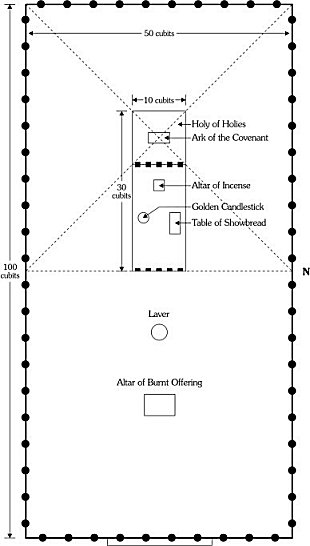

Tabernacle Design and Artistry. The tabernacle, built by the people, under the direction of the God-chosen master craftsmen Bezalel and Oholiab according to a pattern shown by God to Moses, is a tent of wooden frames covered by curtains (30x10 cubits), surrounded by a curtain-enclosed court (100x50 cubits). (See NIV footnotes to chs. 25–28 for modern measurement equivalents).

The tent is divided into the most holy place (or “holy of holies,” 10x10 cubits) and the holy place (20 x 10 cubits), separated from each other by curtains hung on posts. The holiest place contains the ark of the covenant (a chest 2.5 x 1.5 x 1.5 cubits) containing the tablets of the covenant. The ark’s cover, the so-called “mercy seat,” bears a cherub at each end, their outstretched wings embracing an empty space over the ark, the space where the gentile nations would have placed the figure of a god or goddess. Only the high priest, clad in special robes (ch. 28), officiated here, most prominently on the yearly Day of Atonement (yom kippur, Lev 16).

The holy place accommodated the altar of incense, the table of the bread of presence and the lampstand (menorah). The surrounding court contained the bronze basin and the altar of burnt offering. The holy place and the court were the scene of daily rituals and activities of the priests.

Although a tent structure, the tabernacle is described for us as a sanctuary of great beauty. The quality of materials and the artistry of workmanship is finest in the inner sanctum of the tent, the most holy place, from where it descends in quality as one moves to the periphery: the holy place of the tent, and further out to the court surrounding the tent. For example, the finely worked curtains with artistically embroidered symbols such as cherubim are succeeded by works of lesser, coarser fabric further from the center; gold is followed by silver, and then bronze; colors descend in the order of blue, purple, and crimson. Parallel to this, there are especially fine and symbolically decorated robes for the high priest and less elaborate ones for the priests.

Tabernacle Theology. Only in a few places does the biblical text describing the tabernacle accommodate our habitual Western search for rational theological meaning by an explicit verbal interpretive statement. Interpretive meaning must often be deduced from the obvious or less obvious symbolism. For example, carrying-poles, inserted through rings, clearly mean that the sanctuary shall be mobile. God’s presence moves along in the midst of his people, or even ahead of them. The tabernacle has been called suggestively “Mount Sinai on the move.”

The three names used for what we have simply called “tabernacle” so far, provide significant clues. (1) “tabernacle” (Hebrew: miškan) designates a dwelling, a place where one lives for a shorter or longer time. (2) “tent of meeting” (’ohel mo’ed) designates a place of encounter. (3) “sanctuary” (miqdaš) designates a set-apart, holy, sanctified, consecrated place. How these general meanings are to be understood specifically must be derived from the contexts of their occurrences. (For fuller discussion, see Janzen, 2009b).

Theologically central and unmistakable is the tabernacle’s focus on God’s holiness. It is symbolically represented by the small part of the tent set apart as the holiest place (or “holy of holies”). It holds the “ark of the covenant,” a small chest containing the tablets of the covenant law. Its cover is the “mercy seat,” understood as a throne and flanked by the outspread wings of two cherubim. And now, the centre of revelation: Where heathen temples would have the statue or image of a god, representing some aspect of nature, there is empty space. The God of the Bible is transcendent; no part of the created world can ever represent God as the idols of the nations were meant to do. True worship is at its heart an-iconic, imageless (20:4-6). It is a clearing of space for God’s invisible presence.

The high priest alone enters here on the Day of Atonement (traditionally Yom Kippur, Lev 16), silent and barefoot. Only the inscription of the names of the twelve tribes of Israel on his two shoulder pieces and on his breast plate, as well as a golden rosette on his turban with the inscription “Holy to the LORD” express in words that, in the person of this high priest, Israel approaches the invisible Divine Presence. No words, no prayers, no music. Only little bells on the hem of the high priest’s robe alert God, through their faint ringing—a daring anthropomorphism!—that Israel is approaching its God for mercy (the mercy seat) and instruction (the covenant tablets). In the larger part of the tent and in the court around it there is much activity, but at the center, humans become still in the mysterious presence of the transcendent God.

Like the book of Revelation with its symbolism, the tabernacle’s features have spawned lush allegorical interpretation, often going to great excess. And yet, the Tabernacle invites legitimate typological association with Jesus Christ. It prefigures (later in complex association with the Jerusalem temple) the central earthly manifestation of incarnation: God, represented through the materials and designs of this world, yet without being caught up in them, retains a real but elusive presence. God “tabernacling/tenting” among God’s people is properly invoked in the Gospel of John, where we read about Jesus: “And the Word became flesh and lived (literally: "tabernacled”) among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father's only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14; compare Exod 25:8).

The Tabernacle in Exodus. While the Tabernacle texts (25–31; 34–40) in themselves convey a profound theology, their theological meaning is considerably extended when we read them in the context of the whole book of Exodus. The most salient observations in this regard are these:

1. At the beginning of Exodus, we encounter the Israelites as slave builders for a brutal, oppressive, and illegitimate master. In the construction of the Tabernacle (chs. 35–40) they are joyfully volunteering their skills and their goods in the service of the only true Master.

2. This change of masters, however, can only take place after the abortive attempt to replace the Pharaoh by the culturally suggested alternative of an idol, the Golden Calf, an attempt from which only the intercession of Moses and God’s subsequent grace could rescue Israel (32–34).

3. Israel’s wilderness wanderings (chs. 15–17) are marked by the repeatedly surfacing doubt of Moses’ God-inspired leading and the people’s persistent murmuring, that issued eventually in the question hurled at Moses: “Is the LORD among us or not?” (17:7; cf. 32:1). In the last verses of the book, as the glory of the LORD fills the tabernacle, God gives the final answer (34:34-38). That a long history of doubt and covenant breaking will mark Israel’s future, lies beyond the interpretive context of Exodus. The theme of the complex interrelationship of Tabernacle and creation can also not be treated here (see Janzen 2009b).

The Theology of Exodus—A Summary

Exodus is a book about change of masters. It responds, as it were, to the question: Whom shall Israel legitimately serve? Several points summarizing the theology of Exodus should be emphasized, some by way of correcting wrong or limited understandings that are widely held.

God's Saving Initiative and Israel's Response

Exodus is a book about God's gracious initiative and Israel's reluctant response and repeated rebellion. It is this tension that draws the modern reader into the story. Do we look condescendingly at Israel's resistance to God at work, or do we sense in ourselves the same all too human characteristics? In other words, Exodus addresses us in the same manner as the cross of Christ: Would we have been the crucifiers or the cowardly disciples, or would we have responded with a strong faith? But we were neither at Israel's exodus nor at the scene of the crucifixion. The question for us therefore is: To which response do exodus and crucifixion invite us today?

Salvation as Change of Masters

Exodus tells the story of Israel's liberation from Pharaoh, but that is only half the story. Liberation in the modern sense, i.e. the achievement of freedom from someone else's rule in order to be able to follow one's own will and direction, is certainly not in view. Israel is subject to a ruler at the beginning of the book as well as at the end. At issue is the question of Israel's legitimate ruler. Not service versus freedom, but service to a usurping tyrant versus service to the legitimate master is the theme. That the latter is in itself a form of freedom is assumed (see point 4, below).

Commissioning of a People

Exodus is not a book about God's choosing a people for himself. Israel is spoken of as "my [God's] people" from the very beginning (3:7). Nor does Israel become God's covenant partner in Exodus: "God remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob" (2:24). That covenant is assumed, in Exodus, to be valid. What happens at Sinai is a renewal of the Abrahamic covenant through its redirection towards a special commission on Israel's part, namely to be a "priestly kingdom and a holy nation" for the whole world (19:6).

Grace in the Form of Law

Exodus is not a book in which God's unconditional grace, shown to Abraham and the other Ancestors, is replaced by the requirements of law. Whether, or in what sense, the Abrahamic covenant was unconditional cannot be discussed here. In the context of the Sinai-covenant, however, law is not the heavy burden it often seems to Christians to be, but the gift of God's directives for a new and better life under a new master. It is based on Israel's experience of God's gracious deliverance. And when it is transgressed, as it is immediately after the covenant ceremony (ch. 24) by the construction of the Golden Calf, God's grace again prevails over Israel's disobedience (chs. 32–34).

Grace as God's Holy Presence

Grace, however, is not the indulgent leniency of a spineless ruler, but the awesome presence of the holy God in the midst of a people that can live fully and happily only if that presence is properly acknowledged and all of life is oriented towards it.

In sum, Exodus leads from the service of a usurping tyrant to the service of a legitimate and gracious master; from the groaning of slaves to the celebrating of privileged partners. The repeat-reader knows, however, that this is only a temporary moment of "arrival," a sign of the goal of God's leading. The journey will go on, and the struggle will continue. We today participate in that journey, and the book of Exodus clarifies the goal and the options for us.

Conclusion and the Anabaptist Tradition

Background

As part of the Pentateuchal narrative, Exodus has regularly belonged to the stock of Bible stories taught to Anabaptist-Mennonite children. To this stock belonged Israel’s oppression in Egypt, Moses’ preservation in a basket and adoption by Pharaoh’s daughter, his flight to Midian, his call at the burning bush, Israel’s oppression in Egypt and their Moses-led deliverance, the parting of the sea, the miraculous sustenance by God in the wilderness, and the events of covenant conclusion at Mount Sinai, including the giving of the Ten Commandments, soon followed by the idolatrous worship of the golden calf and God’s gracious provision for repentance and restoration

The tabernacle chapters (25–31; 35–40), while a major pre-occupation of some, were probably neglected by the majority of Mennonites. This resulted in a truncated grasp and appreciation of the book of Exodus. Further, the general Anabaptist-Mennonite New Testament orientation also included the sidelining of Exodus (Janzen, 2001). This book was generally neither drawn upon as pointing forward to Jesus, the Messiah, nor found for the most part as particularly troubling from the standpoint of core Mennonite emphases like nonresistance/pacifism, unlike the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua. Among the Exodus laws, only the Ten Commandments were generally held to be significant for Christian living.

Global cultural shifts in more recent times, however, have drawn new attention to Exodus as a potential resource for addressing questions of major importance for the church generally and for special Anabaptist-Mennonite concerns. In addition to new questions surrounding war, violence, and peace, Exodus has elicited new interest in connection with three areas of modern concern: 1) violence and deliverance/liberation. 2) Human violation of ecological and cosmic balance. 3) Restorative versus retributive justice. Only brief sketches can be presented here to identify some resources offered in Exodus in the search to address these.

Violence and Deliverance

Oppression, Persecution, and Genocide

Anabaptists and Mennonites have repeatedly been an oppressed and persecuted group since their beginnings in the 16th century. The Mennonite Story in Russia offers only one prominent example from that story of oppression and persecution. Invited by to that country toward the end of the 18th century by Empress Catherine II with the promise of freedom to live according to their faith, they experienced a gradual erosion of their welcome. Many emigrated to North America in search of greater freedom to live according to their faith. (See Migration as Peacekeeping, below.) When severe oppression began after the Bolshevik Revolution, many more were able to emigrate to the Americas, but then the borders of Soviet Russia were closed and the large remaining numbers were, like the Israelites in Egypt, forcefully detained in the land of their oppression and subjected to expropriation, exile, concentration camps of forced labour, torture, and mass execution in numbers unprecedented in their earlier history. Of the approximately 35 000 who were able to escape to the West during World War II, some 23,000 were—unlike the Israelites escaping from Egypt—recaptured and forcefully “repatriated” to slave labor in desolate parts of Asiatic Soviet Russia. The thematic parallelism to the Israelite story, from Joseph to the exodus, is striking, but this and other Anabaptist-Mennonite stories of oppression, persecution, and deliverance have never or rarely been drawn on by their descendants for their historical and theological identity formation, even though they are replete with faith, trust, and a sense of Divine deliverance or supportive presence.

By contrast, other oppressed populations in our time have drawn heavily on Exodus for theological interpretation of their condition and for visualizing and shaping their own liberation. Thus “liberation theology,” beginning in Latin America, but proliferating in many forms there and elsewhere since the last third of the 20th century, has become a theological household concept. In its biblically oriented forms it has heavily drawn on the book of Exodus for its liberation mandate. Mennonites, in their increasing transformation from inward-turned communities to extensive involvement in relief work and peace promotion around the globe, and due to their rapidly increasing numbers in the southern hemisphere, have also been affected deeply by various aspects of liberation theology. Exodus, if read through Anabaptist-Mennonite glasses, has the potential to enrich such Mennonite global presence and involvement, both by helping to set biblical objectives and by averting or correcting misunderstandings of this biblical book. The following themes are particularly relevant in this area.

Does Oppression Legitimize Violent Liberation?

Does the biblical exodus account model and/or authorize peaceful or violent liberation for oppressed people? The answer is paradoxical. Exodus often presents Israel’s departure from Egypt in military language. In Exodus 1–15, and then briefly again in 17:8-16 and 23:20-33, we note a persistent emphasis on God as warrior fighting on Israel’s behalf and subduing God’s and Israel’s enemies. God’s encounter with Pharaoh is presented as a raging battle. Israel is often pictured in military terminology: It is an army (14:19) of six hundred thousand men on foot (12:37), or better: “men capable of fighting,” with dependents (12:29-39), structured in "(military) companies" (6:26; 7:4; 12:41, 51). They leave Egypt laden with booty plundered from the Egyptians (12:36; 11:2-3). The Israelites are prepared for battle (13:18) and move from one "(military) camp" to another (e.g., 13:20). Nevertheless, with one exception, Israel does not fight throughout its exodus, for—as Moses states—"The LORD will fight for you, and you have only to keep still" (14:14).

In warding off the Amalekites later in the wilderness, Israel does engage in battle (17:8-16), and the occupation of the Promised Land is projected as a march of military conquest (15:13-16; 23:20-33). In both these contexts, however, the emphasis also rests fully on God’s role in defeating the enemies, rather than on Israel’s military strength or achievement. In keeping with all this, the Song of the Sea exalts God’s sole agency in hymnic praise:

- The LORD (Yahweh) is a warrior;

- The LORD (Yahweh) is his name. (15:3; cf. 1 Sam. 17:47; Ps. 24:8)

Such warfare, in which the victory is gained by Yahweh, either without human fighting or with merely token human participation, occurs in many Old Testament texts. Such wars are called by scholars “Yahweh war” or “holy war” [Yahweh War].

Mennonite scholar Millard Lind has pointed to the LORD’s sole agency in the destruction of the Egyptian army in the Red (Reed) Sea as the focus of Israel’s Song of the Sea (15:1-21): “The Reed Sea deliverance forms the paradigm for Israel’s future salvation” (Lind, 1980: 49; cf. 48–54; 1990:182-196). According to Lind, the single most important affirmation of the Song is that Israel, although consistently and deliberately characterized as a victorious army marching out of Egypt, has no fighting role in the battle.

Are we then not to learn any lesson from the Song—and therewith from Israel’s exodus—regarding human warfare? Yes, we are, but I agree with Lind that the lesson for us regarding our armed or military participation in our deliverance from oppression is a negative one. Yahweh “fights” for us, and we are called to “be still.”

Lind goes further by making Yahweh war, as paradigmatically experienced by Israel in the Sea event, the historical cornerstone for an early Israelite pacifism, a calling that was abandoned, according to him, with the establishment of the monarchy of David and Solomon, but continued as a call to Israel in the message of the prophets. It constituted the backdrop for the peace teaching of Jesus and was continued in the early church, only to be compromised—according to John Howard Yoder and others—by Emperor Constantine’s role in drawing the church into an alliance with the state and its power structures, not unlike David and Solomon had done earlier. Anabaptism, according to Lind, Yoder, and others, took up this heritage many centuries later. (Lind, 1980 [with Introduction by John H. Yoder]; 1990: 171-196; Yoder, 1971; 2003; Nugent, 2011).

While I—although a convinced pacifist—have certain reservations regarding this Lind-Yoder vision of “theo-politics,” I do agree with Lind in his claim that Exodus does not present oppression as authorizing human violence as a means to achieve liberation. It is worth noting that the later exodus of the liberated Jewish exiles from Babylon, presented in Isaiah 40–55 in Exodus language and imagery, is also accomplished by God, this time through the agency of the Persian Emperor Cyrus (Isaiah 44:27–45:7), while the Jewish exiles, epitomized by the “suffering servant,” are assigned the role of patient suffering (see especially Isaiah 52:13–53:12), rather than that of liberation fighters.

I do not believe (contra Lind), however, that Israel had a historical pacifist phase where it abandoned itself more or less totally to God’s intervention (through “Yahweh war”) on its behalf. But even if one were to accept Lind’s position, this would not resolve the problem of many New Testament pacifists regarding the wars of the Old Testament, for it would not address the problem of a God who wages or commands cruel wars. Would we really want to attach ontological reality to the warrior-characterization of Yahweh, attributing to God the exercise of a violence that for us is sin? Or is the warrior-language to be understood metaphorically as expressing the highest form of the exercise of authority known to the ancient world, an authority which, in light of the power and authority of the cross and resurrection of Jesus, however, is only partially and inadequately reflected in the warrior image? This appears to me a more adequate hermeneutic for interpreting God’s warrior role in Exodus (and the Old Testament generally) than the search for an originally pacifist historical Israel (Janzen, 1982c; 1984; 2011).

A pacifist position is advocated and practiced by various modern liberation theologians and movements, but rejected by others. Some of the latter seek in Exodus a mandate for the use of violence against oppressors by means of a hypothetical redaction history of this biblical book, in the course of which an original story of a revolutionary uprising on the part of an oppressed minority group or a disadvantaged lower class was supposedly reworked in later times, when Israel had become a monarchy, into a story of Divine redemption. George Pixley, for example, claims: “The fact that the exodus is an act of divine salvation does not militate against its being a human revolution as well, with all the political management a revolution requires. “ (Pixley, 1987: 20. Cf. also 118f., and throughout). I cannot accept his hypothesis as supportable by the canonical text of Exodus.

Liberation Versus Change of Masters

A further tension between the book of Exodus and modern liberation approaches emerges from the widespread contemporary understanding of “liberation” (“freeing,” “setting free”). Modern proponents of liberation, whether secular or religious, frequently mean by this term the escape from someone else’s rule to a state of self-determination, that is, a maximization of individual choice. In the interpretation of “exodus” in this article, by contrast, I have tried to demonstrate that the dominant theme in Exodus is not escape, liberation, but a “change of masters.” (see also Levenson, 1993: 127-159). Israel is delivered from an illegitimate larger-than-life tyrant, Pharaoh, not to self-determination in the understanding of liberal democracies, but to the service of the Master of the universe, God. The “deliverance from” needs the complement of the “deliverance to” in order to complete Israel’s deliverance. “Salvation” is therefore a term more appropriate for Israel’s exodus than “liberation.” Paradoxically, living in covenant with, and serving the only legitimate Master is the only really freed existence.

Migration as Peace Witness

Anabaptists-Mennonites have often undertaken migrations or flights to escape oppressive systems and seek refuge in places where they hoped to worship God according to their conscience. In a world where conformity to political rulers and systems is highly valued, such moves can be associated with lack of patriotism, with cowardice, or even with treason. Rulers and political systems have often forcibly detained, or alternatively, forcibly expelled such “non-conformist” groups. In the Western world, the horrors of World War II and other factors have created a somewhat more lenient and understanding approach to “conscientious objectors,” many countries creating legal options for alternative service. Selective conscientious objection, for example, to the use of atomic or chemical weapons, or to a specific war, finds greater understanding than in earlier times. The designation “draft dodgers” for those who avoided military service in the US engagement in the Vietnam War by escaping to Canada is telling. Although at first used in a pejorative way only, it has eventually become accepted by many as a term for a legitimate conscience-based peace witness. Pacifist migration, if undertaken in obedience to God’s call to peaceful rather than violent resolution of conflicts, must equally be regarded as one option of non-violent resolution in many situations where the alternative would be violence. Still, many people in our world can escape from violent oppression only with great difficulty.

Such escape from the pharaohs of our world, if accomplished, often does not lead immediately to a “promised land,” but rather to some time in the wilderness.

In Exodus, the story of Israel’s wilderness wandering became a story of experiencing God’s special leading, with its high point in God’s theophany and covenant. Thus the context of the wilderness is an essential part of the message of the book of Exodus and the remainder of the Pentateuch. Like the liberation theme, the theme of wilderness wandering central to Exodus and should become a theological resource for interpreting flight, emigration, wandering, and theophany for the many people on the move today as refugees, immigrants, and other uprooted people in our global village, including Anabaptists-Mennonites. Having spent my childhood years under Stalinist oppression in the Soviet Union and my youth as a World War II refugee in Europe before coming to Canada, I can testify that some of my richest and most faith-shaping experiences belong to those “wilderness wandering years” of my life. (For the spiritual dimension of wilderness and the paradigmatic nature of wandering/pilgrimage for Christian existence generally, see Commentary, 212-222; Sanders: 31-53; Williams, 1962.)

Violation of Cosmic Balance (Ecology)

Mennonite Attitudes to Land

Mennonites have for centuries been predominantly people of the land. Due to persecution, and in search of freedom to practice their faith, they have often moved to remote and uncultivated areas, draining the wetlands, clearing the jungle, or plowing the steppes and prairies. Generally, they have neither romanticized nor theologized their relationship to the land, but have viewed their movements and resettlements pragmatically, as means to make a living in contexts allowing for freedom of worship. Often they have been successful, or even become prosperous economically, while at the same time establishing well-ordered social and ecclesiastical structures. Although they acknowledged their dependence on God in both prosperity and adversity, their love for, and stewardship of the land has seldom found overt theological explication, nor has there been explicit attention to what we now call creation care or ecological stewardship until recent times. In this respect, Mennonites have not differed greatly from general Western culture and have often been stragglers in recognizing the need for cosmos care, rather than pioneers. This neglect, as it appears to us today, is undoubtedly a result of the Anabaptist-Mennonite one-sided emphasis on the New Testament, where the Old Testament’s rich land theology, although subtly present, is less explicit. (Janzen, 1992c; 2001). Attention to the rich theological resources of the Old Testament’s land theology could have put our churches, with our avowed biblical orientation and our practical agricultural experience in many lands, into the forefront of ecological concerns.

In view of our threatened ecological planet earth, it is incumbent on us to remedy this neglect, and the book of Exodus offers significant theological impulses to do so. This claim may sound surprising. Traditionally, Christians have associated Genesis with the created order of the cosmos, and Exodus with God’s redeeming activity in history. More recently, however, scholars have pointed out the pervasive presence of the creation theme in Exodus, recognizing the threat to cosmic order inherent in historical injustice, and conversely, God’s engagement of nature in judging oppression and sustaining the redeemed.

Oppression and Anticreational Judgment Phenomena

The Exodus narrative is closely tied to its natural setting and theologically intertwined with it. The descendants of Jacob, driven by famine, settle in the fertile land of Goshen as a result of God’s use of Joseph, not only to preserve their own life during a severe famine, but also the lives of their Egyptian hosts. The descendants of Jacob/Israel live in the fertile area of Goshen, where they prosper and multiply. This is the opening situation of Exodus. But eventually, life-giving fertility of land and people issues in jealousy and fear on the part of Pharaoh, who turns the Nile, Egypt’s life-sustaining water source, into a means of genocide. This is the tyrant’s first “anticreational” act, a term borrowed from Terrence Fretheim, who has prominently highlighted the role of nature in Exodus. (Fretheim, 1991a; 1991b; 1991c.) Moses is saved from the abused waters of the river in an ark, presaging God’s salvific leading of his threatened people through sea and wilderness.

When God’s confrontation of the Arch-Oppressor through God’s prophetic servant Moses (with Aaron) meets hardened resistance, God’s judgment signs (plagues) take the form of the natural order gone awry. In Fretheim’s words: "God gives Pharaoh up to the “natural” consequences of his anticreation behaviors (hardening of the heart being one). . . . The plagues are not an arbitrarily chosen response to Pharaoh’s sins, as if the vehicle could just as well have been foreign armies or an internal revolution. The consequences are cosmic, because the sins are anticreational (Fretheim, 1991a:111; emphasis his).

The intertwining of human sin and cosmic disturbance is a widespread theme in the Old Testament (for example, Isaiah 24:1-13; Jeremiah. 4:23-28; Amos 4:6-12), but we can only trace its main foci in Exodus. To these belongs God’s use of the judgment signs (plagues) and the Red Sea, discussed above. Conversely, not only God’s judgment takes on natural/cosmic character; so also does God’s mercy and blessing. We need only think of God’s provision of healing and of water and food (manna and quails) throughout Israel’s wilderness wanderings, although these sustaining signs can turn into vehicles of judgment when Israel’s disobedience warrants this (16:19-20; further examples in Numbers). Ultimately, God’s sustaining grace looms ahead as the goal of the exodus, the promised land, a goal not realized in Exodus, but kept in view throughout the book.

Ecological threats to our planet and its life have been raised to consciousness throughout our culture in recent decades. Mennonites, too, have been engaged in extending their concerns for peace and justice into the realm of nature care. Drilling of wells to provide water in arid areas, introducing sustainable agricultural methods, reducing of harmful chemicals and emissions of gases, and many other efforts have become part of our church agendas. The Old Testament, and within it, the book of Exodus, can help us to develop a biblically founded creation care ethic, rather than to engage only sporadically in various initiatives coming at us from here and there.

Restorative Versus Retributive Justice

Exodus introduces the theme of law into the biblical narrative. At Mount Sinai, redeemed Israel is called into a covenant relationship of service to its sole legitimate master, the one true God. The covenant binds Israel to God in a new role of service, a service not enslaving, but truly freeing. Israel is to model a God-pleasing life as a witness to the nations. The Law (Torah) conveys God’s instructions for such a life in covenant with God and in community with each other. Mennonites love the concept and language of covenant. They accord the Ten Commandments high respect. But they are ambivalent as to law beyond that, especially Old Testament law. A whole arsenal of suspicions is evoked by it, often in the name of Jesus and the New Testament. Is the Law not the way of the Scribes and Pharisees who constantly challenged Jesus? Is it not the opposite to grace, as Paul supposedly emphasized? Is it not superseded by the New Testament? Should we not simply follow the example of Jesus and the love he taught and lived? Does law not lead to a Scripture interpretation characterized by rigid legalism and proof-texting? And finally: Is it not essentially punitive and cruel, while Jesus taught forgiveness and love of enemies?

Israel’s life as community is first sampled tersely in the Ten Commandments (or Decalogue; in Hebrew: “Ten Words,” Exod 20:1-17). Even these commandments are not abstract, ahistorical principles, but samples of communal life with focus on the extended family, the “Father’s House,” as I have argued. A more extensive and nuanced picture of ancient life under God is offered in the Book of the Covenant (or Covenant Code; Exod 20:22–23:33). The social context for this code is the clan or village community, consisting of several extended families living in a rural, agricultural setting, and its aim is to preserve what we might call “community shalom,” that is, the general harmony and well-being of the community, as well as just ways of dealing with disruptive occurrences. Many of the Code’s “ordinances” (21:1) sound strange, quaint, and sometimes crude or cruel to the modern reader. Historical distance makes this inevitable, and only a detailed study can help us to overcome this strangeness and gain some appreciation. Even a cursory reading at one sitting, however, may impress the sensitive reader with a general difference from a modern Western law code: Though strange in its specific prescriptions, the goal of these laws is not primarily punishment of offenders, or even deterrence of crime, but the well-being of all; the victims, the wrongdoers, and the community as a whole. In more recent parlance: the aim is restorative (healing) rather than retributive (punishing) justice.

Maintenance of community shalom through restorative justice is an old ideal and practice, but only in the last quarter century has such vocabulary become current among Mennonites and others. Howard Zehr’s pioneering work Changing Lenses, first published in 1990, has been in the forefront of a revived interest in this topic among Mennonites and beyond (Zehr, 3rd ed., 2005). Many studies, by Zehr and others, as well as new practices based on them, have since appeared, among them such well-known initiatives as Mediation Services and Victim-Offender Ministries. Zehr himself, in his extensive chapter “Covenant Justice: The Biblical Alternative” stresses the significance of biblical (largely Old Testament) law in the shaping of this vision. (Zehr, 2005: 126-157). We can do no more here than illustrate restorative justice in connection with a small sampling of laws from the Covenant Code.

1. Sometimes restitution simply means that:

- "When someone causes a field or vineyard to be grazed over, or lets livestock loose to graze in someone else's field, restitution shall be made from the best in the owner's field or vineyard" (22:5).

2. Another law shows that, when neglect has caused loss that must be restored, even the guilty one’s welfare is considered:

- "If someone leaves a pit open, or digs a pit and does not cover it, and an ox or a donkey falls into it, the owner of the pit shall make restitution, giving money to its owner, but keeping the dead animal" (21:33-34).

We note that the guilty one must make restoration, but may keep the meat of the dead animal. No punitive element is added.

3. Sometimes a deterring feature is added to restitution, especially where willful wrong is committed:

- "When someone steals an ox or a sheep, and slaughters it or sells it, the thief shall pay five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep" (22:1).

Or:

- "When someone delivers to a neighbor, money or goods for safekeeping, and they are stolen from the neighbor's house, then the thief, if caught, shall pay double" (22:7).

4. If the neglect of the owner of a goring ox has caused human death, the situation is different. He has forfeited his life, deserving the death sentence. But since the death was not intended, the village court may impose a fine instead:

- "If the ox has been accustomed to gore in the past, and its owner has been warned but has not restrained it, and it kills a man or a woman, the ox shall be stoned, and its owner also shall be put to death. If a ransom is imposed on the owner, then the owner shall pay whatever is imposed for the redemption of the victim's life" (21:29-30).

5. Quarrels resulting in fights are inevitable.

- "When individuals quarrel and one strikes the other with a stone or fist so that the injured party, though not dead, is confined to bed, but recovers and walks around outside with the help of a staff, then the assailant shall be free of liability, except to pay for the loss of time, and to arrange for full recovery" (21:18-19).

That a stone or a fist are mentioned, rather than, for example, a dagger, shows that the injury was probably unpremeditated. The roles could easily have been reversed. Both are equally guilty or innocent, but the injured person ought to be cared for.

6. Sometimes our different cultural context makes it hard to understand the intention of ancient laws, as in the following case of sexual seduction:

- "When a man seduces a virgin who is not engaged to be married, and lies with her, he shall give the bride-price for her and make her his wife. But if her father refuses to give her to him, he shall pay an amount equal to the bride-price for virgins" (22:16-17).